| Above: A man walks past a devastated street during floods in Saka, Hiroshima prefecture, on Sunday, July 8, 2018. Image credit: Martin Bureau/AFP/Getty Images. |

The downpours are gone, but western Japan is still reeling from a multiday onslaught of torrential rains, floods, and mudslides that peaked last weekend. At least 176 people have died and dozens remain missing, making this the nation’s deadliest weather disaster since 322 people were killed in floods and landslides across western Japan in July 1982. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited the flood-stricken regions of Okayama prefecture on Wednesday, while hundreds of rescuers were still at work, days after the worst of the flooding. At least 4600 homes were flooded in Okayama, partially as a result of collapsed dikes. The rains have now transitioned to hot, humid weather, exacerbating the stress on survivors.

The disaster’s large death toll prompted Reuters journalist Linda Sieg to ask on Wednesday, “Why did so many die?” Although more than a million people were placed under evacuation orders, some did not know where to seek safety. Others may have believed the storm would not be as bad as it was. The ever-present risk of catastophic earthquakes in Japan has also tended to focus disaster mitigation on seismic rather than hydrological threats.

|

| Figure 1. An aerial view of flooded houses in Kurashiki, Okayama prefecture, Japan, on Sunday, July 8, 2018. Image credit: STR/AFP/Getty Images. |

Heavy rainfall is a normal feature of Japan’s climate in early summer (see below), but the past few days have been extraordinarily wet. Most of the official rainfall data from the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) only goes back to the 1970s. With that caveat in mind, many locations saw their heaviest rainfall on record for various intervals on July 8. The rains were exceptionally heavy on Sunday morning at the two stations below, according to JMA data.

1-hour period:

Sukomo (Kochi prefecture): 108.0 mm (4.25”) , old record 86.5 mm, records begin in 1943

Kanayama, Gero (Gifu prefecture): 108.0 mm (4.25”), old record 86.0 mm, records begin in 1976

3-hour periods

Sukomo (Kochi prefecture): 263.0 mm (10.35”), old record 136 mm

Kanayama, Gero (Gifu prefecture): 185.5 mm (7.30”), old record 138 mm

6-hour periods

Sukomo (Kochi prefecture): 351.0 mm (13.82”), old record 197 mm

Kanayama, Gero (Gifu prefecture): 213.5 mm (8.41”), old record 151 mm

|

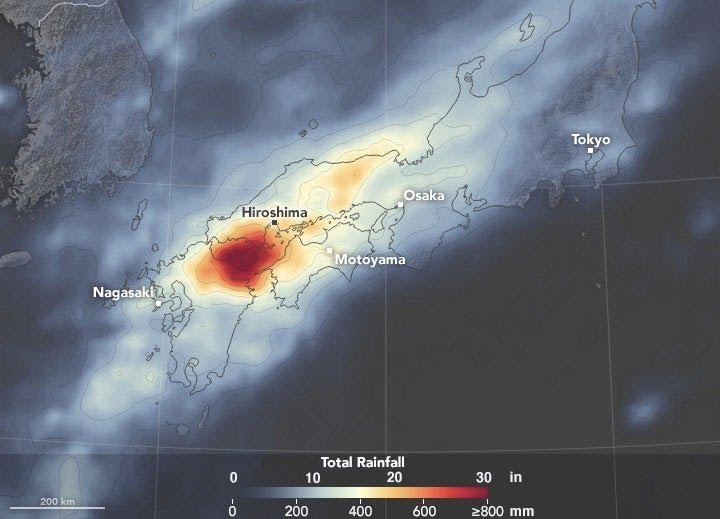

| Figure 2. Rainfall totals for the period July 2-9, 2018, as estimated from data collected by the international Global Precipitation Mission (GPM). Esimated amounts were greater than 500 millimeters (20") over a broad region centered between western Honshu, northern Shikoku, and eastern Kyushu islands. GPM is part of a satellite-based lab program that involves NASA, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, and five other partners. Some local totals may have been even higher than the satellite-derived estimates shown here. Image credit: Joshua Stevens/NASA Earth Observatory, using IMERG/GPM data at NASA/GSFC. |

The meteorological setup

Japan's flood disaster was the result of two common features of Japan’s early-summer climate that teamed up to deliver a one-two meteorological punch.

Round 1: Typhoon Prapiroon. Although it was not especially intense, Category 1 Typhoon Prapiroon set the stage for this month’s flood disaster. Prapiroon angled into the Sea of Japan from the southwest, moving between Japan and South Korea. This put the western and southern parts of Honshu on Prapiroon's stronger southeastern flank, and this trajectory meant that the region would remain moist even after the typhoon had passed by. Satellite-based estimates show that precipitable water, or PW (the amount of water vapor in a column over the ground) averaged a soggy 50-62 cm (about 2” to 2.4”) across and near western Japan on July 3-5, both during and after the passage of Prapiroon.

|

| Figure 3. A day/night visible satellite image of Typhoon Prapiroon at 1648Z (1:48 am July 4 in Tokyo) on July 3, 2018, as the storm was passing just to the north of western Japan. This image was collected by the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) aboard the Joint Polar Satellite System. Image credit: RAMMB / CIRA @ CSU. |

Round 2: The Bai-yu front. After Prapiroon’s departure, several more days of heavy rain were generated by the annually recurring Bai-yu front, which became locked in place over Japan late last week. The Bai-yu (or Mei-yu) front is part of the East Asia summer monsoon, which surges northward each spring and summer and retreats southward in the fall. This zone of contrasting air masses is nurtured by the Tibetan Plateau, as westerly winds are forced to flow around the plateau and then converge downstream, from eastern China to Japan.

The Bai-yu front can sometimes stall out for a period of days or weeks, bringing a prolonged period of clouds and rain. This pattern can be intensified when Japan is located at the southerly back end (or the “right entrance region”) of a strong upper-level jet stream over the Northwest Pacific, which was the case last week.

A small surface low and weak upper-level trough that developed along the front west of Japan on Friday provided an additional trigger for heavy rain and pulled even richer moisture into the area. PW values exceeded 70 mm (2.76") over parts of southwestern Japan as the rainfall intensified on July 6-7, according to analyses produced by Alicia Bentley (SUNY-Albany). Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) have been running 1-2°C (1.8-3.6°F) above average from Japan southward and eastward in recent days (see Figure 4). All else being equal, these warm waters would favor high dew points and rich low-level moisture flowing into the Bai-yu front over Japan during periods of southerly surface winds.

|

| Figure 4. Sea surface temperatures across the Northwest Pacific (degrees C) as of July 11, 2018, relative to the 1981-2010 average for this time of year. A patch of unusually warm water stretches from Japan eastward. Warm waters also extended south of Japan on July 2, as Typhoon Prapiroon was approaching, so the typhoon had even more warm water to work with than shown here. Image credit: tropicaltidbits.com. |

The outlook for Japan

The current weather forecast is a good-news/bad-news proposition for Japan. The odds of heavy rain should be minimized for at least the next week or so, as a strong ridge of high pressure will park itself over the nation. The downside will be a prolonged period of unusually intense heat and high humidity, not unlike a July heat wave in the Northeast U.S. Lows will hover well above 70°F, and daytime highs will regularly soar above 90°F, a few degrees above the seasonal norm, which won't make things any easier for those trying to recover from the devastating floods.