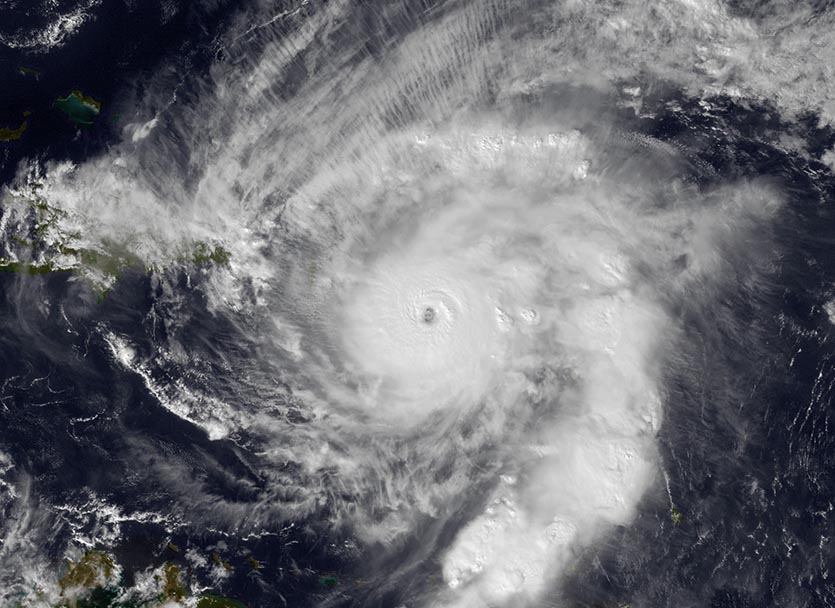

| Above: MODIS satellite image of Hurricane Otto taken at approximately 11 am EST, November 24, 2016--Thanksgiving Day. At the time, Otto was a Category 3 storm with 115 mph winds, about to make landfall in Nicaragua as the strongest and deadliest Atlantic hurricane ever recorded so late in the year. Image credit: NASA. |

It’s been a crazy-busy Atlantic hurricane season in 2017, with the season currently ranking in 10th place for most named storms (16), 8th place for hurricanes (10), 3rd place for major hurricanes (6), and 7th place for Accumulated Cyclone Energy (224). We’re getting near the end of the season, which officially runs until November 30. So, will these be the final tallies, or will we get one or more named storm this year? Since six of the seven years with more ACE than 2017 ended up having at least one more named storm after November 1, past history suggests that an active season like 2017 should see at least one more named storm. Given the latest model output and current atmospheric and oceanic conditions, I predict that we will see one more Atlantic named storm this year--Rina.

|

|

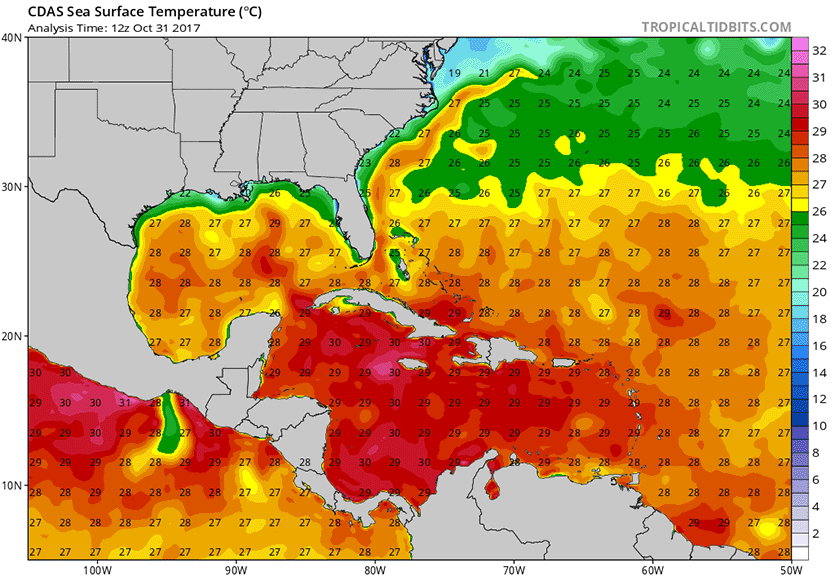

| Figure 1. Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) (top) and departure of SST from average (bottom) in the Atlantic on October 31, 2017. SSTs were above the 26°C (79°F) threshold (yellow and warmer colors) needed to sustain a tropical storm over nearly all of the waters south of Florida’s latitude. These waters were about 0.5°C (0.8°F) warmer than the average from 1981 – 2010. When considering a more representative Twentieth Century SST average, the departure of SST from average was a few tenths of a degree warmer than that. Image credit: Levi Cowan, tropicaltidbits.com |

Forecast through mid-November

The tropical Atlantic is quiet, with no threat areas to discuss, and no reliable models predicting development of a tropical cyclone during the coming five days. The waters of the tropical Atlantic are certainly warm enough to support development, with sea surface temperatures (SSTs) well above the 26°C (79°F) threshold typically needed to support tropical storm formation (Figure 1.) In addition, the large-scale circulation pattern during the first week of November will favor upward-moving air and an increased chance of tropical storm development over the Atlantic, due to the current positioning of the Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO), a pattern of increased thunderstorm activity near the Equator that moves around the globe in 30 - 60 days. The MJO is expected to weaken thereafter, and will neither favor nor suppress Atlantic hurricane activity into mid-November.

According to the latest run of the GFS model, we can expect variable wind shear ranging from low to high over the Caribbean during the first half of November, giving the opportunity for tropical cyclone formation if a source of spin can be found in an area of lower shear. The African Monsoon is quiet this time of year, and we no longer have African waves coming off the coast of Africa that can act as the seeds for formation of a tropical storm in the Caribbean. However, the circulation associated with the Eastern Pacific monsoon trough spawned Tropical Storm Philippe last week, and a similar event could occur after November 10 in the southern Caribbean off the coast of Nicaragua, according to recent runs of the GFS model. Other possible sources of spin for a late-season tropical storm include a lingering non-tropical low-pressure system that gets cut off from the jet stream over the Central Atlantic, or the tail end of a cold front over the Northwest Caribbean stalling out for multiple days over warm waters.

Named storm formation location for all November Atlantic TCs since 1851. Most major hurricanes have come out of western Caribbean. pic.twitter.com/VRQWJRc2HM

— Philip Klotzbach (@philklotzbach) November 1, 2017

Named storm formation location for all November Atlantic TCs since 1851. Most major hurricanes have come out of western Caribbean. pic.twitter.com/VRQWJRc2HM

— Philip Klotzbach (@philklotzbach) November 1, 2017Late-season Atlantic hurricane history

During the active Atlantic hurricane period 1995 through 2016, a total of 20 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes formed in November or December, with 14 of those 22 years (64%) having one or more of these late-season named storms. The busiest year was (no surprise) 2005, when four November/December named storms formed (Gamma, Delta, Epsilon, and Zeta.) Here are all the late-season named storms since 1995 and their formation dates:

2016: Major Hurricane Otto (Nov 20)

2015: Hurricane Kate (Nov 8)

2011: Tropical Storm Sean (Nov 8)

2009: Hurricane Ida (Nov 4)

2008: Major Hurricane Paloma (Nov 6)

2007: Tropical Storm Olga (Dec 11)

2005: The "Greek" storms: TS Gamma (Nov 14), TS Delta (Nov 22), Hurricane Epsilon (Nov 29), and TS Zeta (Dec 30)

2004: Tropical Storm Otto (Nov 29)

2003: TS Odette (Dec 4), and TS Peter (Dec 7)

2001: Hurricane Noel (Nov 5), and Hurricane Olga (Nov 24)

1999: Major Hurricane Lenny (Nov 14)

1998: Hurricane Nicole (Nov 24)

1996: Hurricane Marco (Nov 19)

Six of these storms (30%) caused loss of life: Hurricane Otto of 2016, which killed 23 in Central America; Hurricane Ida of 2009, which killed one boater on the Mississippi River; Tropical Storm Olga of 2007, whose floods killed 24 on Hispaniola and 1 in Jamaica; Tropical Storm Gamma, which killed 34 people in Honduras and 3 in Belize; Tropical Storm Odette of 2003, whose floods killed eight people in the Dominican Republic; and Hurricane Lenny of 1999, which killed fifteen people in the Lesser Antilles. There have been only eight major Category 3 or stronger hurricanes in the Atlantic after November 1; "Wrong-way Lenny" was the strongest hurricane on record to form in November (Category 4, 155 mph winds). Note, though, that the 1932 Cuba Hurricane, which formed in October, was stronger: it achieved Category 5 strength (175 mph winds) on November 6, 1932. For more on these famous late-season storms, see weather.com’s write-up, Five Unforgettable November Atlantic Hurricanes.

Part of the reason for the relatively low loss of life for November storms is their location: they tend to form from extratropical low-pressure systems that get cut off from the jet stream and linger over the warm waters of the central subtropical Atlantic, far from land, then end up recurving northeastwards out to sea.

|

Figure 2. The strongest hurricane on record in the Atlantic to form in November, Hurricane Lenny, takes aim at the Lesser Antilles on November 17, 1999. At the time, Lenny was a high-end Category 4 hurricane with 155 mph winds. Image credit: NOAA. |

Late-season Atlantic hurricanes are occurring more often

It used to be that late-season hurricanes were a relative rarity--in the 140-year period from 1851 - 1990, only 30 hurricanes existed in the Atlantic on or after November 1 (some of these formed in late October, but existed as a hurricane in November.) This works out to an average of one late-season hurricane every five years. Only four major Category 3 or stronger late-season hurricanes occurred in those 140 years, with only three Caribbean hurricanes. But in the past 26 years, late-season hurricanes have become nearly three times more frequent--there have been 17 late-season hurricanes, 6 in the Caribbean, with 4 of these being major hurricanes. While some of this increase can be attributed to better satellite detection of storms in recent decades, I expect that warmer ocean temperatures due to global warming are also a contributing cause.

Global warming could be causing a longer hurricane season

The Atlantic hurricane season does appear to be getting longer in the Atlantic south of 30°N and east of 75°W, according to Dr. James Kossin of the University of Wisconsin. In his 2008 paper in Geophysical Research Letters titled, "Is the North Atlantic hurricane season getting longer?" he found an "apparent tendency toward more common early- and late-season storms that correlates with warming sea surface temperature, but the uncertainty in these relationships is high". A 2016 analysis by Dr. Ryan Truchelut of WeatherTiger also supported this idea. However, Juliana Karloski and Clark Evans of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee found no trend in tropical cyclone formation dates when looking at the entire Atlantic, for the period 1979 - 2014. A 2015 study of season length in climate models led by MIT’s John Dwyer yielded mixed results, depending upon which model was used to simulate hurricane activity.

Volatile Earth: Killer Hurricanes airing Wednesday night on PBS NOVA

If you need a break from tonight's World Series Game 7, at 9 pm EDT PBS NOVA is airing "Volatile Earth: Killer Hurricanes." The show will focus on the Great Hurricane of 1780, the deadliest Atlantic hurricane on record (over 22,000 killed), and how climate change is making such violent high-end hurricanes more likely. I should have a few minutes of air time in the show, as they spent an entire day filming me last year for it. I recounted my near-fatal flight into Hurricane Hugo in 1989 for them, and discussed how a tornado-scale vortex embedded in the eyewall was likely responsible for our misfortune. There is also a separate NOVA hurricane show focusing on Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria coming out in February, for which I did another day of filming two weeks ago.