| Above: A burned neighborhood is seen in Paradise, California, on November 15, 2018. Image credit: Josh Edelson/AFP/Getty Images. |

The death toll from California’s horrific Camp Fire, which broke out on November 8 and devastated the northern California town of Paradise, has held constant at 86 victims over the past week, and the search for more remains has been discontinued. Of the 86 people who have been killed, 41 have been positively identified with another 42 tentatively identified. Thankfully, the list of those missing had shrunk to just 25 by Monday, down from the peak of 1276 that had been reported missing on November 17.

With its death toll of 86 (with no more than 113 deaths possible, if all of those missing are presumed dead), the Camp Fire will end up as the fifth deadliest wildfire in U.S. history, and 12th deadliest in world history. The last time the U.S. had a deadlier fire was 100 years ago—the Cloquet Fire of 1918 in Minnesota, which killed an estimated 453 people (note that some official death tolls from that disaster were 1000, but that was an erroneous estimate, according to an excellent November 22 story from The Mercury News).

The Camp Fire was the most destructive fire in California’s history, with 18,804 buildings destroyed—more than three times higher than the previous record of 5636 structures destroyed in the October 2017 Tubbs Fire in California’s Wine Country. The Tubbs Fire, in turn, was nearly twice as destructive as the previous record holder, the October 1991 Tunnel Fire in the Oakland Hills, which consumed an estimated 2900 structures.

Monetary damage from the Camp Fire has been estimated at $11 - $13 billion by CoreLogic, which would challenge the $13 billion price tag of last year’s Wine Country fires as the most expensive wildfire in world history. (CoreLogic also estimated that total losses from the Woolsey Fire near Malibu in Southern California, which erupted on the same day as the Camp Fire, would be an additional $4 billion to $6 billion, making it the third costliest wildfire in world history.) Fifteen of the twenty most destructive fires on record in California have occurred since 2002. The 153,000 acres the Camp Fire burned puts it in 16th place for largest fire in California history. Fifteen of the twenty largest fires on record in California have occurred since 2002.

This year's fires in California have pumped 15% more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than the state usually emits.

|

| Figure 1. The aftermath of the October 1918 fire in Cloquet, Minnesota, that killed 453 people. Image credit: University of Minnesota, Duluth, Kathryn A. Martin Library. |

No U.S. agency keeps official tallies of the nation’s wildfire deaths, but EM-DAT, the international disaster database, has global wildfire statistics going back to 1911. Using their data, plus additional information from other official and unofficial sources, here is a list of all U.S. wildfires on record that have killed at least fourteen people:

- 1200-2500 deaths, 1871 (Peshtigo Fire, Wisconsin)

- 453 deaths, 1918 (Cloquet Fire, Minnesota). Sometimes erroneously stated as 1000 deaths (as in EM-DAT)

- 418+ deaths, 1894 (Hinkley Fire, Minnesota)

- 282 deaths, 1882 (Thumb Fire, Michigan)

- 88 deaths, 2018 (Camp Fire, Paradise, California)

- 87 deaths, 1910 (Great Fire of 1910, Idaho and Montana)

- 65 deaths, 1902 (Yacolt Burn, Oregon and Washington)

- 29 deaths, 1933 (Griffith Park Fire, Los Angeles, California)

- 25 deaths, 1991 (Tunnel Fire, Oakland Hills, California)

- 22 deaths, 2017 (Tubbs Fire, California)

- 19 deaths, 2013 (Yarnell Fire, Arizona)

- 16 deaths, 1947 (The Great Fires of 1947, Maine)

- 15 deaths, 2003 (Cedar Fire, San Diego County, California)

- 15 deaths, 1953 (Rattlesnake Fire, California)

- 15 deaths, 1937 (Blackwater Creek Fire, Wyoming)

- 14 deaths, 2017 (Gatlinburg, Tennessee)

- 14 deaths, 1994 (South Canyon Fire, Colorado)

Below is the top twenty-five list of deadliest wildfire events globally prior to the Camp Fire, along with the Camp Fire itself. It is sobering to note that we have seen a resurgence in very deadly fires in the 21st century, after seeing a notable absence in the middle and late 20th century. The recent resurgence is largely due to our increased vulnerability (more people living in the wildland/urban interface) plus more extreme fire weather (hotter, drier heat waves due to human-caused climate change), plus bad luck.

- 1200 - 2500 deaths, 1871 (Peshtigo Fire, Wisconsin)

- 1200 deaths, 1936 (Kursha-2 Fire, Soviet Union)

- 453 deaths, 1918 (Cloquet Fire, Minnesota)

- 418+ deaths, 1894 (Hinkley Fire, Minnesota)

- 282 deaths, 1882 (Thumb Fire, Michigan)

- 240 deaths, 1997 (Indonesia forest fires)

- 223 deaths, 1916 (Great Matheson Fire, Ontario, Canada)

- 191 deaths, 1987 (Black Dragon Fire, China and Soviet Union)

- 180 deaths, 2009 (Black Saturday bushfires, Australia)

- 160 deaths, 1825 (Miramichi Fire, New Brunswick, Canada)

- 126 deaths, 2018 (Attica, Greece)

- 88 deaths, 2018 (Camp Fire, California)

- 87 deaths, 1910 (Great Fire of 1910, Idaho and Montana)

- 82 deaths, 1949 (Landes Fire, France)

- 75 deaths, 1983 (Ash Wednesday bushfires, Australia)

- 73 deaths, 1911 (Great Porcupine Fire, Ontario, Canada)

- 71 deaths, 1939 (Black Friday bushfires, Australia)

- 65 deaths, 2007 (Greece)

- 65 deaths, 1902 (Yacolt Burn, Oregon and Washington)

- 64 deaths, 2017 (Portugal)

- 62 deaths, 1967 (Tasmania, Australia)

- 60 deaths, 1929 (Mexico)

- 57 deaths, 1991 (Indonesia)

- 56 deaths, 1992 (Nepal)

- 53 deaths, 2010 (Russia)

- 50 deaths, 1998 (Mexico)

Logged forests burn more intensely than protected forests

President Donald Trump, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke and Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue have all used the fires as an excuse to push for more logging in U.S. forests, saying that would cut the fire risk. However, a 2016 paper, Does increased forest protection correspond to higher fire severity in frequent‐fire forests of the western United States? found that just the opposite is true—the latest scientific data shows that forests with the highest levels of protection from logging tend to burn least severely. Chad Hanson, a forest ecologist who was one of the co-authors on the paper, said in an interview with The Guardian: “Donald Trump and Ryan Zinke are being dangerously dishonest. They are trying to use this tragedy to help logging interests, which is one of the most disgusting things I’ve seen in my career. They are trying to eliminate half a century of environmental protections and turn over forests to the logging industry.”

It is true, though, that many of our forests have too much fuel as a result of decades of fire suppression efforts, and that we need to reduce the fuel loads of these forests. A bipartisan advisory group, the California Little Hoover Commission, released a February 2018 report regarding forest management in the Sierra Nevada. A key way to reduce fire danger, they concluded, was to increase the use of prescribed burns. They also said that “appropriate management will result in trees being removed from the forest. When possible, this wood should generate income for forest management.”

Deadly wildfires are the result of a very complex mix of factors, and perhaps the most effective step we can take to reduce the death tolls is to build more fire-proof structures and do a better job defending existing structures against fires, argued fire expert Stephen Pyne in a November article in slate.com. The National Fire Protection Association’s Firewise program shows how to harden houses and create defensible space without nuking the scene into asphalt or dirt.

An encouraging start to the water year in California

California’s wet season, which officially started October 1, is off to a moist start that’s good news for reducing fire risk over the coming months. Autumn rains were slow to arrive from far northern California to western Washington: Crescent City, CA, had its twelfth driest October-November in 125 years of recordkeeping. However, for much of California, the last two months have brought at least near-normal rains. Downtown San Francisco saw 3.77” for the Oct.-Nov. period, the 107th-wettest such period in the 169 years since records began. Downtown Los Angeles received 2.15”, its 104th-wettest Oct-Nov. in 142 years of recordkeeping.

|

| Figure 2. Annual precipitation for the period from October 1 to November 30 in downtown San Francisco (top), where records began in 1849, and downtown Los Angeles (bottom), where recordkeeping began in 1877. Image credit: NOAA/xmACIS2. |

A fairly cold and wet storm in late November pushed the Sierra Nevada well above average for the water year thus far in terms of moisture stored in snowpack (snow water equivalent). Snowpack moisture can vary greatly from week to week and month to month, depending on both temperature and the frequency of storm systems. We are still very early in the high-country wet season: on average, the Sierra has built up only about 10-15% of its annual snowpack by early December.

The pattern across the United States over the next few days is starting to look more and more like an El Niño pattern, which makes sense given the embryonic El Niño conditions expected to hold sway this winter. The main jet stream will flow across the southern two-thirds of the nation for at least the next week, bringing periodic bouts of rain and mountain snow to California and perhaps a major winter-type storm from the mid-South to the mid-Atlantic late this week.

|

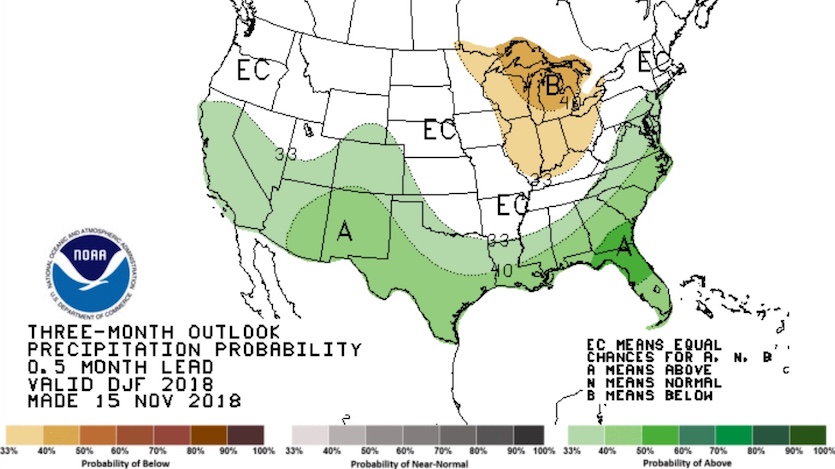

| Figure 3. Winter precipitation outlook (Dec. 2018 - Feb. 2019), showing where odds favor above- or below-average amounts. In areas labeled "EC", the probabilities of above-, near-, and below-average precipitation are each 33%. The odds of a wet winter are a few percent higher than usual across California, and they are enhanced even more across most of the nation's southern and southeastern tier. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/WPC. |

In the longer range, NOAA is calling for enhanced odds of a wet winter from California across the Sun Belt (see Figure 3), in line with typical outcomes for an El Niño. That said, the slight odds-shifting influence of a fairly weak El Niño is far from a guarantee of a wet winter across California, as documented well by Jan Null (Golden Gate Weather Services) in his breakdown of winter precipitation by El Niño strength and California regions.

Bob Henson co-wrote this post.

Our previous post, Court Forces University of Arizona to Release Climate Scientists’ Traditionally Confidential Emails, has helped raise nearly $5000 for the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund. This amount has been doubled in effectiveness to $10K, thanks to the matching gift currently in place. Thanks for your support, everyone who donated, and if you haven’t done so, please consider a contribution!