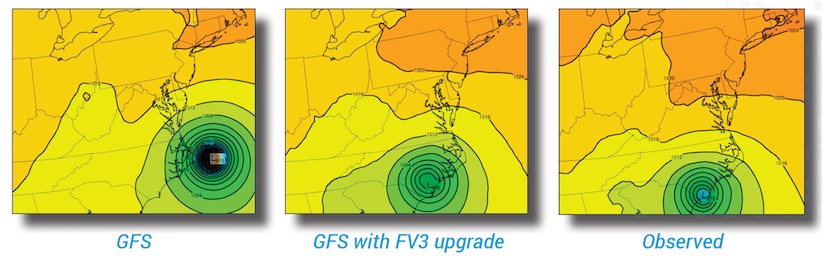

| Above: This geocolor image from NOAA's GOES-East satellite shows the well-defined eye and outermost cloud bands of Hurricane Florence beginning to approach the Outer Banks at 10:45 a.m. EDT on September 12, 2018. At this point, Florence was still a Category 4 storm with 130 mph winds; the winds decreased to Cat 1 strength by the time Florence reached North Carolina. Improvements to the NOAA GFS model yield a far more realistic depiction of Florence’s U.S. approach (see Figure 3 below). Image credit: NOAA/NESDIS. |

A major upgrade to the global workhorse in NOAA’s suite of numerical weather prediction models became official on Wednesday. The Global Forecast System (GFS) has switched to a new dynamical core for the guidance it generates, which extends out to 16 days (384 hours) and is updated every 6 hours. Tests show that the new finite-volume cubed-sphere dynamical core (FV3)—which has been running in test mode since last year—will bring a number of improvements to prediction of various weather features, including tropical cyclones.

“This is a major milestone in our ongoing effort to deliver the very best forecast products and services to the nation,” said acting NOAA administrator Neil Jacobs in a press briefing on Wednesday.

FV3 is the biggest core change to NOAA’s flagship global weather prediction model since it was introduced as the Global Spectral Model in 1980 and reconstituted as the GFS in 2002. FV3 will also serve as the anchor to NOAA’s Next Generation Global Prediction System (NGGPS). The system “will be the foundation for the operating forecast guidance system for the next several decades,” said NOAA in a 2014 summary paper that kicked off the NGGPS development.

As of Wednesday, the new GFS was running operationally with a version of FV3 that addressed several bugs that gained notice earlier this year, including a tendency to run too cold in the lower atmosphere and to produce unrealistically high snow totals in some situations. “We’re seeing a reduced cold bias, but [it] hasn’t been completely eliminated,” said Brian Gross, head of the Environmental Modeling Center (EMC) at NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Prediction, at the press briefing.

|

| Figure 1. Rather than narrowing at a point, as traditional model grids do at the North and South poles, the FV3 finite-volume cubed-sphere grid converges onto a inlaid higher-resolution grid that can be located as desired on the globe. In the example shown here, the higher-resolution grid is positioned to include Hurricane Sandy while it was near the Bahamas in October 2012. Image credit: NOAA/GFDL. |

What FV3 means for hurricane forecasting

Gross summarized the potential of the new fifteenth version of the GFS for handling tropical cyclones more skillfully than previous GFS incarnations. “Overall we are seeing an improvement in hurricane track prediction across all of the hurricane basins around the world,” Gross said at Wednesday’s press briefing. “We are also seeing improvements in the prediction of intensity as well. We’re looking to benefit from this upgrade on both hurricane track and intensity.”

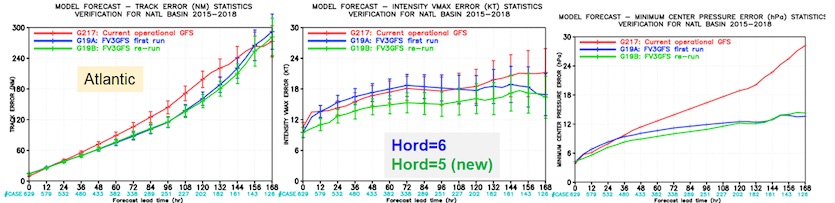

—Improved track forecasts. FV3 marks another step forward in the steady progress in track forecasts, whose error has been cut by more than half since the 1990s. In tests for the Atlantic seasons 2015, 2016, 2017, and the early part of the 2018 season, the average track error with FV3 at four days out was less than 120 nautical miles (140 miles), compared to more than 140 nautical miles with the “old” GFS. The tweaks made to FV3 in early 2019 added slightly to the track improvement (see Figure 2 below). One concern from Figure 2 is that beyond day 6, the old GFS did better on track accuracy than the the FV3-based version—something worth keeping in mind as the National Hurricane Center moves toward seven-day forecasts. Tests for the Atlantic also showed that the track benefits accrued largely to weaker tropical cyclones, so FV3's performance on hurricanes versus tropical storms and tropical depressions will bear watching in 2019 and beyond.

|

| Figure 2. Comparison of the performance for tropical cyclones of the GFS model as of 2018 (blue) with the original FV3 (blue) and the updated FV3 (green). The updated version is the one that became the operational GFS on Wednesday, June 12, 2019. Variables shown are track error, in knots (left); error in peak storm intensity, in knots (center); and error in minimum central pressure, in hPa (right). The study period includes the 2015, 2016, and 2017 Atlantic seasons, as well as the 2018 season through August 17, up through and including Ernesto. Image credit: NOAA/EMC. |

—Improved intensity forecasts. Forecasters have struggled to make consistent improvements in predicting hurricane intensity, which hinges on small-scale features that are difficult for models to reproduce (especially global models). The first version of FV3 showed only marginal changes in predicting the peak winds of a tropical cyclone, but the update now in use shows error reductions in the Atlantic of 2-4 knots at most time periods (see Figure 2 above).

Much of this improvement appears to stem from a more accurate depiction of central pressure. The previous version of the GFS was known for overdeepening the most intense storms, resulting in implausibly deep cyclones with unrealistically weak winds.

“The new FV3 simulations are much closer to the best track wind-pressure relationship, likely a result of improved numerics and physics in the current FV3 model,” said Philippe Papin, a postdoctoral researcher at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory who specializes in tropical cyclones. “I don't think we will see as many sub 900-hPa tropical cyclones associated with less-than-120-kt winds that were common in the old GFS runs.”

|

| Figure 3. In September 2018, Hurricane Florence peaked at Category 4 strength while heading toward North Carolina from the subtropical Atlantic. At one point, the GFS model predicted that Florence would have a central pressure of 915 mb—typical of a Category 4 or 5 hurricane—while just off the Outer Banks (left). In test mode, the FV3 model (center) correctly predicted that Florence would be far weaker as it neared the coast (right). Florence made landfall as a Category 1 storm, though its slow movement and large circulation still produced enormous havoc, causing at least 30 deaths and producing more than $24 billion USD in damage. Image credit: NOAA. |

Challenges that remain

“Every upgrade is going to come with some strengths and some weaknesses,” observed Gross at the press briefing.

Papin notes that the way that FV3 handles convection and cumulus clouds (cumulus parameterization) is unchanged from the previous GFS. He says this is one reason why an unrealistically large number of early-season hurricanes tend to appear in long-range GFS output for the Caribbean, where a predominant large-scale gyre may include pockets of spin (vorticity) that the model erroneously develops.

According to Levi Cowan, a graduate student at Florida State University and longtime WU member who created the tropicaltidbits.com site, “the most significant problem both models have (since 2017) is ‘fake’ gridscale convection in some situations that can lead to false or misplaced TC genesis.”

The new FV3 makes some big strides toward reducing the number of "boguscanes", according to NOAA/EMC physical scientist Fanglin Yang. The center's evaluation found that the FV3 reduces the false-alarm rate for tropical cyclogenesis by 48% in the Atlantic and 33% in the East Pacific, as compared to the previous GFS. The probability of detection—the likelihood that the model will pick up on an incipient tropical cyclone that goes on to develop—dips slightly in both basins, which is a common side effect of improving false-alarm rates in models.

"Overall, false alarms for TC genesis are reduced in v15 [the new FV3-based GFS] but remain an issue," Yang said. "This is consistent with the idea that the convective scheme plays a major role in genesis, and it is mostly unchanged compared to v14."

In Cowan's view, “FV3GFS has shown slight statistical improvement in [tropical cyclone] forecasts during re-runs, but it remains to be seen whether the model will ‘feel’ more reliable during real-time cases in terms of things like run-to-run consistency, vortex behavior, and storm intensity.”

Benefits beyond the GFS

The adoption of FV3 will benefit not only the GFS itself but also the Hurricane WRF (HWRF), a shorter-range model based on a high-resolution “nest” driven by GFS output. HWRF is already among the best-performing models for predicting tropical cyclone intensity.

FV3 was developed at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory. Another of the candidates for the new GFS dynamical core—the Model for Prediction across Scales, developed at the National Center for Atmospheric Research—is now serving as the foundation of the IBM Global High-Resolution Atmospheric Forecasting System, or GRAF (see our post from January).

Special thanks to Fanglin Yang, Avichal Mehra, Zhan Zhang, and Geoffrey Manikin for background on the FV3 evaluation.