| Above: Antique cars, part of a collection, lie in rubble in a devastated neighborhood on Monday, July 29, 2018 near Redding, California. Image credit: Gianrigo Marletta/AFP/Getty Images. |

The most destructive July wildfire on record for California has consumed more than 900 structures and killed at least 6 people, including two firefighters. The Carr Fire, which began on Monday, July 23, grew explosively on Thursday night, ripping into the foothills near Redding, and continued expanding into the weekend. As of Monday morning, the fire was 20% contained after having consumed 98,724 acres and 966 structures, according to CAL FIRE.

Although eight other California fires have destroyed more structures, all of those occurred later in the dry season, from September onward, including the traditional late-summer/early-autumn core of the state’s fire season.

Other fires plaguing the state include the Ferguson Fire near Yosemite National Park. Two firefighters have died on the scene of the Ferguson blaze, one on July 14 and the other on July 29. The Ferguson Fire prompted Yosemite’s largest fire-related closing since 1990. As of Monday morning, the fire had scorched 56,659 acres and was 30% contained.

We are saddened beyond words to report the death of Captain Brian Hughes of the Arrowhead Hotshots. Hughes' crew was on the #FergusonFire on @Sierra_NF when he was struck and killed by a tree. We grieve his loss.

— Sequoia & Kings Cyn (@SequoiaKingsNPS) July 30, 2018

Photo courtesy of Brad Torchia pic.twitter.com/Lwy2MyH1jN

For the U.S. as a whole, including Alaska, wildfires have burned 4,632,398 acres as of Monday. That’s the fourth-highest year-to-date total in records going back to 2008, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. The total acreage burned so far this year is about 25% above the ten-year average. The 98 large fires active as of Monday have burned a collective total of 1,214,777 acres.

|

| Figure 1. The Air Quality Index (AQI) was in the “unhealthy” range (red) across much of northern California and southern Oregon downwind of the Carr fire at 3 pm PDT Sunday, July 29, 2018. In Yosemite National Park (just north of Fresno on the map), the AQI was in the “very unhealthy” (purple) range. Image credit: EPA/AirNOW. |

Dangerous air quality in California

Smoke from the ongoing fires is bringing dangerously high levels of fine particulate pollution (PM2.5, particles less than 2.5 microns or 0.0001 inch in diameter) to portions of California, Oregon, and Nevada. It’s a good thing Yosemite National Park is closed, because on three consecutive days, July 26 – 28, hourly levels of PM2.5 pollution peaked above a suffocating 400 μg/m3, thanks to smoke from the Ferguson fire. The 24-hour PM2.5 standard is 35 μg/m3, and a PM2.5 levels in excess of 251 μg/m3 is considered “hazardous”—the highest level on the Air Quality Index (AQI) scale. The highest 24-hour PM2.5 levels in Yosemite were 161 μg/m3 on July 28, which is solidly in the purple “very unhealthy” range. At this level, EPA warns to expect “Significant aggravation of heart or lung disease and premature mortality in persons with cardiopulmonary disease and the elderly; significant increase in respiratory effects in general population.” Smoke levels were not quite as intense in northern California from the Carr fire, but a large swath of northern California and southern Oregon has been in the red “unhealthy” range for multiple days since the fire began.

Wildfire smoke contributes to tens of thousands of deaths each year in the U.S.

A July 2018 paper by Colorado State's Bonne Ford and co-authors estimated that wildfire smoke contributed to 17,000 premature air pollution deaths each year in the U.S. in the year 2000. This number was expected to rise to 44,000 deaths per year by the year 2100, if we follow a “business-as-usual” approach to climate change (RCP8.5 scenario), which would lead to a steady increase in U.S. wildfires. For the period 1997 – 2006, Johnston et al. estimated an average of 339,000 premature deaths occurred each year worldwide due to inhalation of wildfire smoke; Koplitz et al. (2016) found that the death toll from the air pollution associated with the 2015 Indonesian forest fires alone was over 100,000. Since these causes of death are also due to other factors—such as lifestyle and family history—we typically refer to air pollution deaths as premature deaths. A premature air pollution-related death typically occurs about twelve years earlier than it otherwise might have, according to Caiazzo et al., 2013.

They’re mountains in this shot but they’re hard too see for all the smoke #FergusonFire. pic.twitter.com/hozSQZXjXa

— Jim De La Vega (@JimDeLaVega1) July 30, 2018

Climate change, landscape, and the Carr Fire

Destructive wildfires have been plaguing California over the past year with little apparent heed to the calendar. In October, the Santa Rosa/Sebastopol area endured the state’s deadliest fire of this century and its most destructive on record: the Tubbs Fire, which killed 22 people and destroyed more than 5,600 structures. And the Thomas Fire—the state’s largest since modern recordkeeping began—ravaged more than 281,000 acres in Ventura and Santa Monica counties in December. These fires occurred in seasonal windows that are naturally fire-prone, but with the risk boosted last autumn by a slow start to the wet season.

“There used to be a rhythm to this, and you could at least count on that rhythm,” California firefighter Brian Rice told the New York Times. “It’s a year-round cycle now.” Every month since 2012 has seen at least one wildfire burning in California, noted the Times, citing state officials.

The Redding area has been relatively hot and dry since mid-spring, and especially hot this July, a time of year when it’s normally bone-dry anyhow. The area is on track for its third hottest July in 126 years of recordkeeping, topped only by 1931 and 1933. At the Redding Airport, where observations begin in 1986, this month will very likely beat July 1988 as the hottest of any month on record.

|

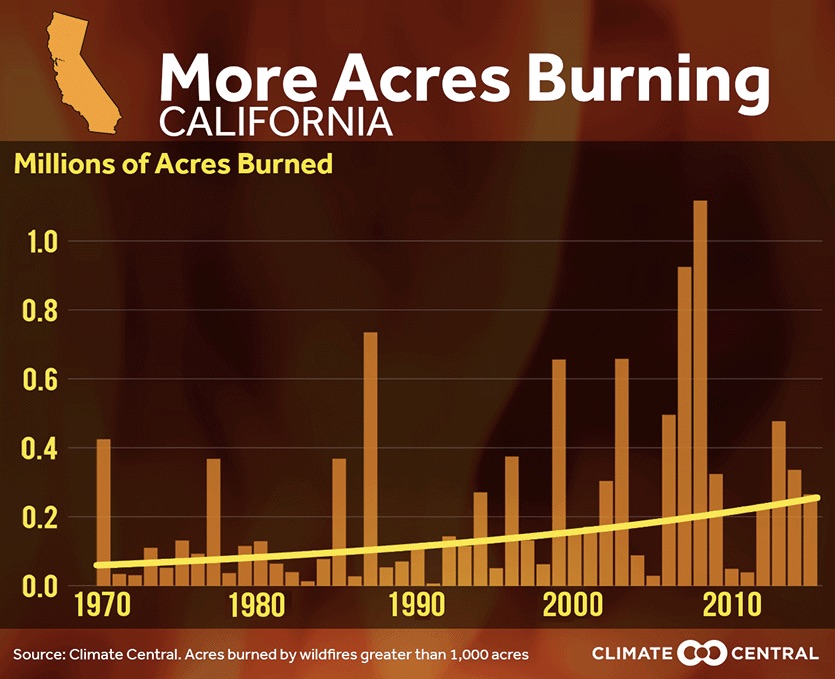

| Figure 2. The number of acres burned in California has been increasing since 1970, due to a warmer and drier climate, in combination with fire suppression policies that have left more fuel to burn.. The average length of the wildfire season in the western U.S. is more than 3 months longer than in 1970, largely due to climate change, according to Climate Central. |

Drought and heat both play into the intensification of California’s fire threat. The state’s annual temperature has climbed by about 2.5°F in the last 50 years. Meanwhile, the state lurched from a grinding drought in 2011–16 to one of the wettest winters on record in 2016-17, then back to a relatively dry winter in 2017-18. That’s not unheard of, given California's Mediterranean climate, but today's dry periods aren’t the same as before. Back in the early 20th century, California experienced both “cool droughts” (with temperatures running below average) and “hot droughts” (temperatures trending above average). Nowadays, California’s major droughts are much more likely to be hot ones. Research led by Noah Diffenbaugh (Stanford University) has linked this shift to human-produced climate change. Hotter temperatures raise the amount of moisture pulled out of the landscape, leaving more fire-friendly conditions.

What the heck is going on with California wildfire situation? Vegetation moisture in many areas now at/near record low levels. Why? Persistently hotter than avg. temperatures, plus dry winter. Map via NW Clim. Toolbox: https://t.co/cbOMwqHBiy #CAwx #CAfire #CarrFire #RiverFire pic.twitter.com/mD2muQKL4f

— Dr. Daniel Swain (@Weather_West) July 29, 2018

The immediate preconditions for fast-spreading wildland fire are the same as they’ve always been: strong winds and hot, dry air moving through parched vegetation. As Jeff Masters recently noted, this month’s deadly wildfires in Greece (where the death toll has now hit 91) occurred in a summer featuring near-average precipitation and hot-but-not-record-hot temperatures. What drove the extreme fire behavior in Greece was unusually strong, hot west winds topping 60 mph.

|

| Figure 3. The Carr Fire rages near Redding, California on Friday, July 27, 2018. Image credit: Josh Edelson/AFP/Getty Images. |

Likewise, what put the Carr Fire into overdrive on Thursday and Friday was a day of extreme heat (Redding tied a daily record high of 113°F on Thursday) coupled with erratic, gusty winds. New research led by Janice Coen (National Center for Atmospheric Research) shows how very localized high winds—including those that emerge from an intense blaze itself—can stoke extreme fire behavior even when winds across the surrounding area are relatively light. KQED has an excellent explainer on the unusually large and strong "fire whirl" that developed on the Carr Fire Thursday night.

Wildfires are shaped not just by the natural environment but also by how and where people live and work. Increasing numbers of Americans are living in or near regions known as the wildland-urban interface (WUI). These are typically scenic places where subdivisions have been built in or near forests, taking advantage of the natural beauty but putting people close to fire-prone areas that are difficult to keep safe. High wind can carry burning embers far ahead of a wildfire, quickly lighting up neighborhoods well away from a fire front. Redding’s population has soared from around 17,000 in 1970 to around 90,000 today, and the city has pushed northwestward in recent decades into the picturesque, forested Cascade foothills.

Increased population in the wildland-urban interface also makes it more likely that human activity will lead to fire, either intentionally or inadvertently. The Carr Fire began on Monday when a vehicle experienced mechanical trouble about 30 miles west of Redding, as reported by SFGate.com.

Dr. Jeff Masters wrote the air-quality section of this post.