| Above: This infrared image of Hurricane Hector and its large eye was collected by NASA’s Aqua satellite at 1225Z (8:25 am EDT) Thursday, August 9. Image credit: NASA/GSFC. |

As we approach the peak of Northern Hemisphere hurricane/typhoon season, the tropics are spitting out plenty of named storms—but as a whole, they aren’t packing much power. As of early Thursday, we had one tropical storm in the Atlantic (Debby), two in the Northeast Pacific (John and Kristy), and two in the Northwest Pacific (Shanshan and Yagi). None of these were expected to pose any major threat to land. The only powerhouse in the mix with these tepid systems was Hector, still raging across the central tropical Pacific as a Category 3 major hurricane.

|

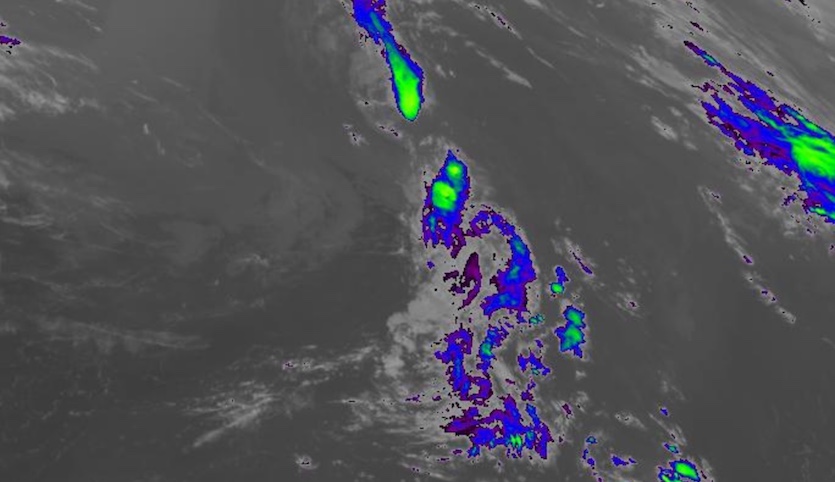

| Figure 1. Infrared image of Tropical Storm Debby as of 2045Z (4:45 pm EDT) Thursday, August 9, 2018, just before it was declared post-tropical. Image credit: NASA/MSFC Earth Science Branch. |

Debby heads for high latitudes

Fast-morphing Debby was reclassified as a post-tropical cyclone at 5 pm EDT Thursday in the National Hurricane Center’s final advisory on the storm. Debby emerged as a subtropical storm on Tuesday from a nontropical system that had been spinning over the central Atlantic, then was reclassified as a tropical storm on Wednesday. On Thursday evening, Debby was centered about 500 miles east of St. John’s, Newfoundland, accelerating toward the northeast at 23 mph. Debbie’s circulation was rapidly shearing, with only a few remnant showers and thunderstorms (convection) still present.

As noted by Dr. Jeff Masters, Debby’s formation date of August 7 comes a little over two weeks earlier than the usual August 23 formation date of the Atlantic’s fourth named storm. So far in 2018, we’ve had 4 named storms, 2 hurricanes, and no intense hurricanes; that is the level of activity typically seen by August 28.

No named systems are expected to develop in the Atlantic through at least early next week.

John and Kristy prowl the East Pacific

After peaking as a Category 2 hurricane off the Mexican coast, John is now a gradually weakening tropical storm. As of 5 pm EDT, John was located about 560 miles west-northwest of Cabo San Lucas, heading west-northwest with top sustained winds down to 65 mph. John’s convective core is now dwarfed by its large, broad circulation, and the convection will wane even further as John moves over progressively cooler waters below 24°C (75°F). High surf from John, including swells up to 8 feet, will slam into the Southern California coast over the next couple of days. Rip currents are also a threat, as noted by weather.com’s Linda Lam.

|

| Figure 2. Tropical Storms John (upper right) and Kristy (lower left) at 2100Z (5 pm EDT) Thursday, August 9, 2018. Image credit: NASA/MSFC Earth Science Branch. |

John’s circulation is helping to goose the North American Monsoon, which has been sending pulses of moisture across the U.S. Southwest in recent days. Localized intense thunderstorms are possible over the next several days in Arizona and New Mexico, especially in areas that get enough sunshine to maximize the instability from surface moisture. These storms will pose a flash flood risk, particular across areas where wildfires have left burn scars. The thunderstorms could also spawn haboobs—intense dust-packing downdrafts that can plow miles ahead of their parent thunderstorms. A massive haboob struck Phoenix last Thursday, August 2.

Well southwest of John—about 1400 miles west-southwest of Cabo San Lucas—Kristy was holding steady with top winds of 65 mph as of 5 pm EDT Thursday as it drifted north at 7 mph. Kristy isn’t the best-organized tropical storm ever seen, but with a broad shield of convection, low wind shear, and adequately warm sea surface temperatures around 27°C (82°F), it’s possible Kristy will become a hurricane before heading further north over cooler waters and weakening this weekend.

Kristy and John may rotate briefly around each other, as suggested by the last several runs of the GFS model, provided they get close enough (around 750 miles apart) for the Fujiwhara effect to kick in. Both storms would be on the downgrade by this point, but Kristy could help prolong the effects of John on SoCal surf and monsoonal moisture. The European and UKMET models keep Kristy to the southwest of John, which would preclude the Fujiwhara possibility.

Hector keeps on keeping on

Now in its fifth day as a major hurricane, Hector continued westward on Thursday, moving deeper into the central Pacific after its center passed about 160 miles south of Hawaii’s Big Island of Hawaii on Wednesday. It’s the closest approach to the Big Island by a Category 3 or stronger storm since Hawaii became a state (although devastating Hurricane Iniki struck Kaua'i as a Cat 4 in 1992).

The eye of Category 3 Hurricane #Hector tracked just 160 miles south of the Big Island of #Hawaii last night... the last major hurricane to pass so close to the island was Dot in 1959! Full loop at https://t.co/vWICHS7kHl @UMiamiRSMAS @capitalweather pic.twitter.com/D3fJpBTvZL

— Brian McNoldy (@BMcNoldy) August 9, 2018

Hector dropped from its peak strength of 155-mph high-end Category 4 sustained winds on Tuesday to low-end Category 3 winds of 115-mph by late Wednesday. Now that Hector has completed an eyewall replacement cycle, however, its strength has ramped back up to 120 mph as of 5 pm EDT Thursday. Hector was located about 530 miles east of Johnston Island (Kalama Atoll), an unincorporated U.S. territory, moving just north of due west at 16 mph.

A large upper-level high will keep Hector pushing westward for the next day or two. After that point, a weakness between this high and another in the northwest Pacific could allow Hector to angle more toward the northwest. A tropical storm watch has been issued for Johnston Island; although it lies well south of Hector’s projected path, the island could still experience at least gales and heavy surf, especially if Hector’s northward angling is delayed on Friday.

|

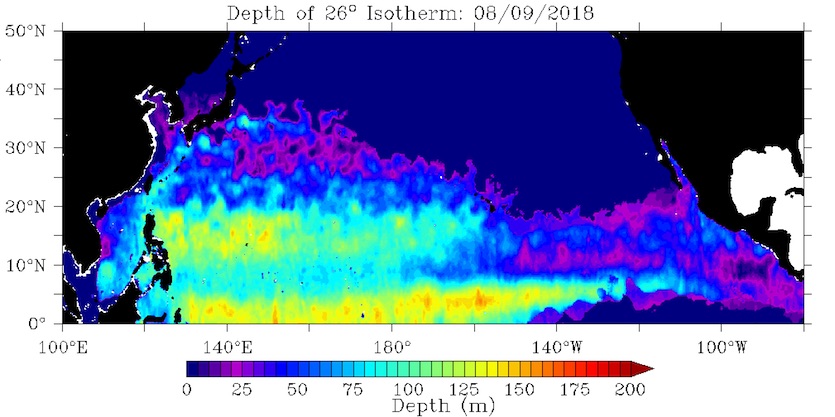

| Figure 3. As long as it heads mainly west or west-northwest, Hector will remain over waters warmer than 26°C (79°F) that extend to some depth. Tropical cyclones typically require SSTs of at least 26°C in order to maintain themselves. Image credit: NOAA/OSPO. |

Long-range GFS model runs continue to suggest that Hector could remain a hurricane until it reaches the International Date Line early next week. If so, it would become Typhoon Hector, entering the rarefied league of tropical cyclones that have maintained hurricane strength in all three North Pacific basins: Northeast, Central and Northwest. Hector also has the potential to rack up more than two weeks as a named storm (it was dubbed Hector on August 1).

The longest-lived tropical cyclone in world history was another Eastern Pacific hurricane that crossed the Date Line and became a typhoon: Hurricane John of 1994. John followed a 7,165-mile (13,280-km) path from the eastern Pacific to the western Pacific and back to the central Pacific, lasting 30.0 days as a tropical cyclone. John brought a few heavy rain showers and high surf to Hawaii, and caused $15 million in damage to U.S. military facilities on Johnston Island. For more on the longest-lived and farthest-tracking tropical cyclones on record, see this weather.com roundup.

|

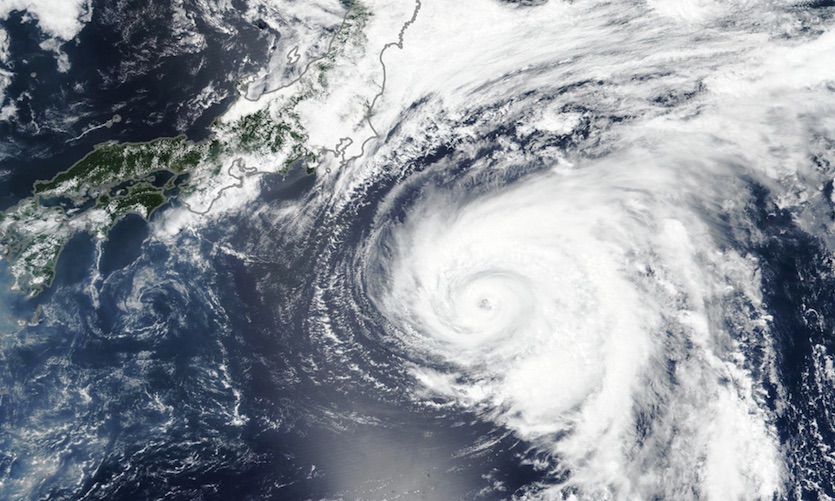

| Figure 4. On August 6, 2018, the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the Suomi NPP satellite acquired this image of Typhoon Shanshan approaching the coast of Japan. Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory. |

A trio of Northwest Pacific systems

Former Typhoon Shanshan gave the Tokyo area a lucky break this week, as it carved a path far enough east of the megacity to keep impacts limited. Four injuries related to Shanshan occurred on Wednesday, reported the Japan Times, and rains of up to 157 millimeters (6.18”) fell in the mountains outside Tokyo as Shanshan’s circulation moved by. Shanshan was rapidly dissipating on Thursday afternoon EDT as it raced east-northeast away from Japan.

Two other systems in the Northwest Pacific bear watching. Yagi is predicted by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center to remain a tropical storm for the next five days as it arcs into the East China Sea, perhaps recurving across the Korean Peninsula. On such a track, even a tropical storm could drop 3-6” of rain in short order on parts of the peninsula, as suggested by the GFS model.

Yet another system in the Northwest Pacific, Invest 96W, may dump enormous amounts of rain on parts of the south China coast, including Hong Kong. This disturbance is not currently expected to go beyond tropical storm strength, as wind shear will remain moderate to high. However, 96W already has a broad shield of rich moisture, and it will be moving slowly within weak steering currents over very warm SSTs of 30-31°C (86-88°F). The result could be rainfall amounts well above 300 mm (10”) in the vicinity of 96W, which may end up anywhere from Hainan to Hong Kong over the next several days.

|

| Figure 5. Graphic illustrating NOAA’s updated hurricane outlook, issued on August 9, 2018. Image credit: NOAA. |

NOAA hikes its odds of a below-average hurricane season

In a unsurprising but noteworthy move, NOAA’s hurricane outlook for 2018 now calls for a 60% chance of a season that’s quieter than average. Those odds were only 25% back in May, when NOAA last updated its outlook. The odds of an average season have dropped from 40% to 30%, and the likelihood of a busier-than-average season are down from 35% to just 10%.

NOAA’s latest expected count for the 2018 season is 9 to 13 named storms, 4 to 7 hurricanes, and 0 to 2 major hurricanes. As explained in the detailed version of the outlook, NOAA sets these “likely” brackets to encompass the 70% probability range; in other words, there’s about one chance out of three that the final number in a given category will be higher or lower than the given range.

A couple of factors that NOAA expects will help keep this season suppressed:

—Unusually low sea surface temperatures in the Main Development Region (MDR) of the tropical Atlantic. SSTs were 0.48°C below average for June-July in this region, the lowest values recorded since the Atlantic entered a multidecadal active period in the mid-1990s.

—The expected presence of a developing El Niño this autumn, which will favor reinforcement of the high wind shear that’s prevailed over the MDR.

Dr. Jeff Masters contributed to this post.