| Above: Indian residents (lower right) look out from their home next to a fallen electricity line following a severe thunderstorm in Agra in northern India's Uttar Pradesh state on May 2, 2018. Image credit: AFP/Getty Images. |

Dust-packed high winds emanating from a huge severe thunderstorm complex tore down trees and damaged homes across north-central India on Wednesday night local time. At least 100 deaths have been reported from the winds, tying it with April floods in Kenya that have also claimed 100+ lives as Earth's deadliest weather-related disaster of 2018. The storm complex hit especially hard in India's Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan provinces, with some of the worst damage in villages near the city of Agra, home to the renowned Taj Mahal. At least 43 deaths were reported from the Agra district, among the total of at least 65 deaths in Uttar Pradesh and at least 35 in Rajasthan.

The destruction appears to have resulted from the strong winds bringing down trees and damaging structures, many of which were poorly designed to handle high winds and flying debris. The storm’s late-night timing likely increased the death toll, since many residents were asleep and caught unaware. Frequent lightning accompanied the high winds, as can be seen in the embedded video below.

|

| Figure 1. Indian residents look at a wall damaged by high winds on Thursday, May 3, 2018, following the storm in Agra district in northern India's Uttar Pradesh state on May 2. Image credit: AFP/Getty Images. |

How did such a storm happen?

Although the Indian calamity has been blamed on “dust storms” in many media reports, the winds were actually thunderstorm-related. In South Asia as the United States, spring is severe weather season. Moist inflow from the Bay of Bengal can travel northwestward up the Ganges Valley into northeast and north central India, sometimes clashing with dry air from western India beneath a westerly jet stream. The resulting thunderstorms may congeal into large-scale overnight mesoscale convective systems (MCSs), the state-sized thunderstorm clusters familiar to residents of the U.S. Midwest.

|

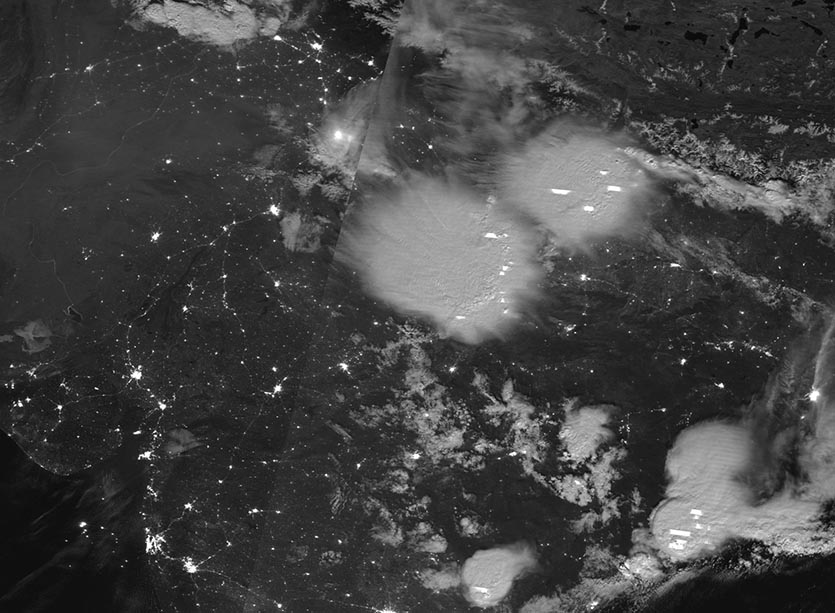

| Figure 2. Nighttime imagery under moonlight from the day-night band of the VIIRS instrument on the Suomi satellite on May 2, 2018, showing an intense thunderstorm (center of image) that caused deadly winds over the Agra province of north central India. The location of city lights is overlaid on the image. This weather.com article has an infrared satellite loop of this storm complex. The embedded tweet below shows the same complex from a different perspective, looking toward the west from the east. Image credit: NASA. |

#Himawari visible view of some of the explosive convection in northern #India that contributed to the unfortunate casualties there on 2 May. Note that up is roughly West in this view pic.twitter.com/jcNsV2R3eW

— Dan Lindsey (@DanLindsey77) May 3, 2018

When warm, dry air infiltrates an MCS several miles above ground level, it can help generate very strong downburst winds at the surface, as the moisture within the storm leads to evaporative cooling of the inflowing dry air. Temperatures have been very hot for this time of year across and west of North India, which may have facilitated strong downbursts. On Monday, temperatures reportedly hit 50.2°C (122.4°F) in Nawabshah, Pakistan, about 120 miles northeast of Karachi and about 600 miles west of Agra. If confirmed, this will be the hottest temperature ever measured on Earth during the month of April, as reported by Brian Kahn at Earther.

Because winter and early spring are typically very dry across northern India, any high winds can generate plenty of dust. As an MCS matures, its high winds can push well ahead of any rainfall, which means that the first impact one might notice from an approaching MCS in this region could easily be from strong, dry, dusty winds.

|

| Figure 3. A forward-propagating MCS is driven by strong upper-level winds (often warm and dry) pushing into the storm from the rear. As moisture evaporates into the winds, they descend to produce powerful downburst winds at the surface. The surface winds may eventually outrun the core of the storm complex itself. The most severe of these events, called derechoes, can last for hours and traverse hundreds of miles, producing widespread damage. It is not clear yet whether the deadly windstorm over India on May 2, 2018, would qualify as a derecho. Image credit: NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center. |

Jeff Masters and Nimitt Jhaveri contributed to this post.