| Above: People enjoy the warm weather in Piccadilly Gardens on April 19, 2018 in Manchester, United Kingdom. Thursday was the UK's warmest April day in almost 70 years, with temperatures topping 84°F in London (see bottom of post). Image credit: Photo by Christopher Furlong/Getty Images. |

From Montana to Maine, millions of Americans are sick and tired of an April that’s been masquerading as February. If you’re one of them, there is hope on the horizon: a push of much milder air will envelop the Midwest and Northeast U.S. over the next few days. The UK Met Office also has an outlook that practically screams “warmer conditions to come”. The only catch is that you’ll have to wait a few years to see if that one is right.

Each year since 2012, the Hadley Centre (the research arm of Britain’s weather service) has issued an outlook projecting global temperature out to five years. This isn’t quite as far-fetched as it sounds. Because water is so much more dense than air, the global patchwork of warmer- and cooler-than-average ocean conditions at any point in time has a lot of influence over both short-range weather and longer-range climate.

Scientists at the Hadley Centre have squeezed forecast value out of ocean observations by coupling them with a variant of the UKMET atmospheric model used for weather forecasts. This hybrid system also incorporates airborne gases and particles (both human-produced and volcanic) and solar variability. The scientists note that “the forecast outcome, at least in first few years, is likely to be dominated by natural variations in the climate system, predominantly from the 'weather' in the oceans.”

A good forecast: the global heat wave of the mid-2010s

The Hadley Centre outlook from early 2014 had a clear view of the handwriting on the wall: “…it is possible that new global temperatures are expected to maintain the record warmth that has been observed over the last decade, and furthermore that it is possible that new record global temperatures may be reached in the next five years.” New global records promptly followed in 2014, 2015, and 2016.

The latest outlook, issued in January, predicts that 2018 will fall short of a new record for global temperature, mainly because of the second-year La Niña event that’s now waning. However, the outlook sees a good chance of a return to record global warmth, perhaps as soon as 2019 or 2020. Over the next five years, it foresees a tendency for the persistent cold pool in the far North Atlantic to return to more normal conditions—a shift that could favor Atlantic hurricane development.

|

| Figure 1. Predicted global average surface temperatures (blue) and observed temperatures (black), expressed in departures from the 1850-1900 average. The model used to predict future temperatures shows skill at reconstructing past temperatures based on prevailing ocean conditions at five-year starting points from 1960 onward (red shading, with the confidence range shown). Observed temperatures are based on Met Office Hadley Centre, NASA/GISS, and NOAA/NCEI analyses. The green band shows reconstructions from 22 model runs, each from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 5 (CMIP5), that were not initialized with ocean conditions. All data are rolling 12-month mean values. The gap between the black curves and blue shading arises because the last observed value represents the period November 2016 to October 2017, whereas the first forecast period is November 2017 to October 2018. Image credit: UK Met Office/Hadley Centre. |

|

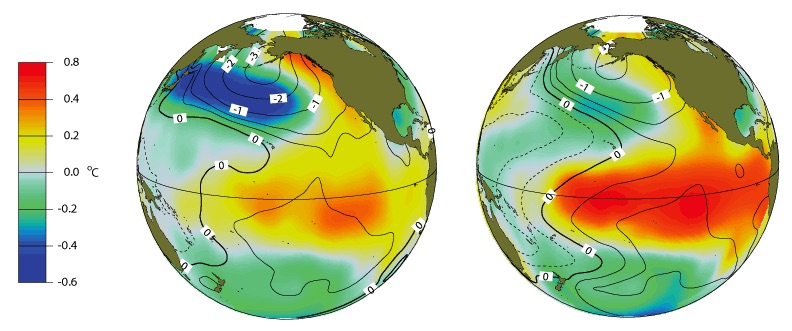

| Figure 2. Observed (A) and issued forecast (B) of surface temperature differences (°C) relative to 1981-2010 for the 5-year period November 2012 to October 2017. Forecasts consist of 10 ensemble members starting from November 2012. The stippling shows where the observations lie outside of the 5-95% confidence interval of the forecast ensemble. The UK Met Office notes: “Although there are differences in the precise magnitude and location of anomalies the observations generally lie within the forecast uncertainty range. However, the forecast was generally cooler than observed in the Southern Ocean, the North Atlantic sub-polar gyre and the North Pacific.” Image credit: UK Met Office/Hadley Centre. |

Watching for the next El Niño

El Niño and La Niña are the main shapers of periodic peaks and dips in global temperature that ride like surfers atop the wave of longer-term warming caused by human-produced greenhouse gases. Of all the heat being trapped by these added gases, the world’s oceans are absorbing more than 90% of it, with just a few percent going into the atmosphere. As a result, only a small change in the ocean’s heat uptake can make a big difference in how much enters the air.

During El Niño, extra heat goes from ocean to atmosphere as the eastern tropical Pacific sea surface warms up. During La Niña, the same region cools down, and less heat enters the atmosphere. An ingenious animation from Dana Nutticelli and skepticalscience.com illustrates how the long-term warming trend becomes much more clear-cut when El Niño and La Niña are factored out.

With this knowledge in hand, you don’t need a sophisticated computer model to tell you that the warmest years of the next decade will most likely occur during El Niño. And climatology tells us to expect an El Niño episode every 3 to 7 years. It’s looking increasingly probable that the next one will kick in later this year, although it might still hold off till 2019 (or later). The latest probablistic outlook issued April 12 by NOAA and Columbia University gives 45-50% odds of El Niño by the end of 2018, with around a 40% chance of neutral conditions and a 13% chance of La Niña.

Not all parts of the world warm up during El Niño, but the northern U.S. typically does. El Niño’s classic effect on North American winter is to mute the usual north-south contrasts, as the polar jet stream retreats far to the north and the subtropical jet strengthens. The prototypical result is a warmer-than-average winter from the northern U.S. into Canada, with cooler-than-average conditions across the Sun Belt. The early springs of 2013 and 2014, which featured some intensely cold weather in the Midwest and Northeast, occurred while the eastern tropical Pacific was slightly cooler than average (though just shy of the La Niña threshold).

What the PDO tells us

The odds of more El Niño than La Niña events may get a boost over the next decade or more if the Pacific Decadal Oscillation has anything to do with it. You can think of the PDO as a cousin of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO). The PDO varies on shorter time scales than ENSO, but it also tends to favor either its warm mode (correlated with El Niño) or its cold mode (correlated with La Niña) for periods of about 15 to 30 years each.

|

| Figure 2. Typical warm and cool anomalies in sea-surface temperature during positive PDO years (left) and El Niño years (right). The patterns are similar, though with differences in intensity over some regions. The anomalies are reversed for negative PDO and La Niña years. Image credit: University of Washington Climate Impacts Group. |

In the title of a February 2015 post, we asked “Are we entering a new period of rapid global warming?” At that point, the PDO was showing hints of a transition into a long-term positive mode after being in a negative mode since the late 1990s. During the 15 or so years in between, La Niña predominated, extra heat went into the ocean, and the pace of atmospheric warming slackened. This was often misinterpreted as a warming slowdown across the entire Earth system, including the oceans—or even worse, that “global warming stopped in 1998!”

As of March, the PDO has (just barely) ended a 50-month positive streak that’s unprecedented in records going back to 1900, according to data kept by Nate Mantua (NOAA). Using a slightly different calculation, NOAA finds that the PDO has been mainly in cool territory since late 2017. Either way, the PDO’s warm phase has predominated during the last four years.

|

| Figure 4. The NOAA/NCEI version of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation index. Shaded bars added to the original NOAA graphic show where multiple studies agree that the PDO switched modes. Since around 2014 (far right of graphic), a warm mode has predominated. The PDO is associated with increased global warming during its warm phase and decreased warming during its cool phase, atop the longer-term warming from human-produced greenhouse gases. Image credit: Base graphic courtesy NOAA/NCEI. |

If in fact the PDO is in a long-term warm phase, it suggests an increased likelihood of El Niño events and a good chance of more record-warm years well into the 2020s, as indicated in the latest UK Met Office outlook.

Time for a beach holiday in Europe?

Only a few weeks after enduring a frigid block of high pressure known as the "Beast from the East," much of Europe will be luxuriating in a few days of remarkable warmth. The United Kingdom saw its warmest April temperature in nearly 70 years on Thursday. The high of 29.1°C (84.4°F) at St. James Park in London was just a shade below the nation's all-time April record of 29.4°C (84.9°F) set in north London (Camden Square) on April 19, 1949. With an expected high of 23°C (73.2°F), Sunday's London Marathon could be the warmest on record, prompting the race's medical director to warn participants via email about wearing "fancy dress" (i.e., heavy costumes).

The dome of heat extended well into the continent, as reported by Capital Weather Gang. Paris hit at least 28.7°C (83.7°F) on Thursday, its earliest-in-the-year reading of at least 28°C (82.4°F) since 1949.

If you are planning a weekend away, northern and eastern Europe are set to turn a little cooler through the weekend, but temperatures are set to climb across Spain and Portugal pic.twitter.com/45tVbLti27

— Met Office (@metoffice) April 20, 2018

In stark contrast, Chicago has done no better than 73°F all spring. Chicago’s average high for the last week of April is around 63°F, but the city will struggle to hit or exceed that mark next week, even with the warm-up at hand.

Adding insult to injury, Chicago had seen six calendar days this month with measurable snowfall as of April 19. The only April to exceed that dreary count was 1910, with seven days.

Many U.S. locations have experienced their coldest start to any April on record (see Figure 5). The long-awaited warm-up—or at least a "mild-up"—could moderate readings just enough to keep at least some of these spots from ending up with a record-cold April, although a top-five-coldest is a safe bet. In any event, the first half of April 2018 will stand as a frigid bookend to the two weeks around New Year's 2018, which were also the coldest on record for many of the same locations.

|

| Figure 5. Ranking for average temperature during the period April 1-18, 2018, as compared to all Apr. 1-18 periods on record, going back in most cases more than a century. Those marked 1 have experienced their coldest Apr. 1-18 period on record this year. A few locations in New York and New England (not shown) also saw their first-, second-, or third-coldest Apr. 1-18 on record. Image credit: Southeast Regional Climate Center. |