| Above: Infrared image of Typhoon Noru at 1330Z (9:30 am EDT) Wednesday, August 2, 2017. Image credit: CIMMS/SSEC/UW-Madison. |

No longer a super typhoon, the long-lived Typhoon Noru remains a significant threat to parts of southern Japan as it makes its way slowly through the Northwest Pacific. Noru is about to enter its third week as a tropical cyclone. Born on July 20, it reached Category 2 status on the Saffir-Simpson scale three days later, weakened, then rapidly intensified to become a fearsome Category 5 typhoon on July 30.

As of 6Z Wednesday, Noru was a Category 3 storm located about 350 miles west-northwest of Iwo To (Iwo Jima), moving northwest at about 7 mph. Noru was packing top (1-minute) sustained winds of 100 knots (115 mph), according to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC). The European and GFS model runs from 0Z Wednesday agree that Noru will angle toward the west-northwest and should reach the northern Ryukyu Islands by Saturday. An approaching upper-level trough over northern China should then bend Noru back toward the north or northeast early next week, potentially threatening the much larger Japanese island of Kyushu.

|

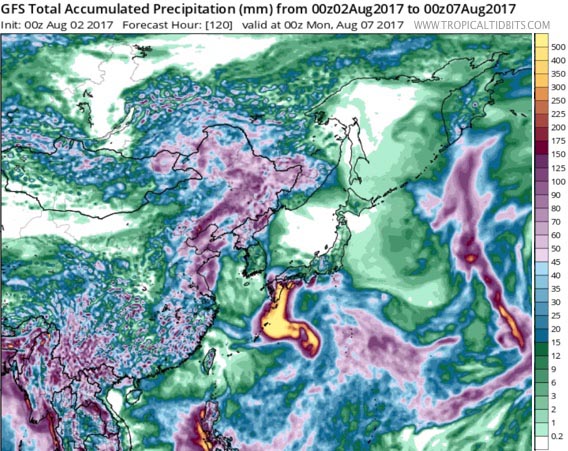

| Figure 1. 5-day forecast of cumulative rainfall produced by the 0Z Wednesday run of the GFS model. Parts of Japan are projected to receive at least 500 mm (19”). Image credit: https://www.tropicaltidbits.com/analysis/models/. |

Noru’s envelope of convection (showers and thunderstorms) is a bit less impressive than it was earlier in the week, and the storm has become somewhat elongated northeast to southwest. Still, wind shear remains light (5-10 knots) atop warm sea surface temperatures (28-29°C or 82-84°F), which is adequate to support a strong typhoon. Noru will be approaching a region of even warmer sea surface temperatures south of Japan over the next several days, with readings of 30-31°C (86-88°F). This should help give the typhoon a short-term boost, although interactions with land and increasing wind shear of 10-20 knots will be countervailing factors. Global models such as the GFS and European are likely continuing to overintensify Noru near Japan—a common problem in midlatitudes, as we discussed on Tuesday. The 06Z Wednesday run of the HWRF, our most reliable intensity model, keeps Noru at its current strength, with a slight weakening just before it reaches southern Japan.

The biggest concern with Noru may be torrential rains, as the slow-moving mature typhoon interacts with rugged topography. The 0Z Wednesday GFS run projects more than 500 mm (19”) of rainfall over eastern parts of Kyushu (see Figure 1). The 06Z run of the HWRF model, though, keeps the heaviest rains offshore from Japan.

|

| Figure 2. Typhoon Noru at 0405Z (12:05 am EDT) August 2, 2017. At the time, Noru was a Category 3 storm with 115 mph winds. Image credit: NASA. |

The Atlantic and Eastern Pacific go quiet

For the first time since July 7, when the tropical depression that became Hurricane Eugene formed in the Eastern Pacific, the National Hurricane Center is not issuing any tropical cyclone advisories for active storms. Both the Atlantic and Eastern Pacific have gone quiet, thanks to the demise overnight of Emily in the Atlantic and Irwin in the Eastern Pacific. The Atlantic has gone hurricane-free for its first five named storms, which is a bit unusual—but by no means a record. In 2011, the last time we used 2017's list of names, each storm fell short of hurricane status until we got to the ninth storm of the season, Irene, in late August—and Irene became one of the ten costliest hurricanes in U.S. history. This year's list features Irma in place of the now-retired Irene.

NHC made two mentions of Atlantic systems with a near-zero potential for tropical cyclone formation in their 8 am Wednesday Tropical Weather Outlook: a small area of low pressure in the Gulf of Mexico, and a tropical wave in the Central Atlantic midway between the coast of Africa and the Lesser Antilles Islands. Dry air is keeping both of these systems from developing much in the way of organized heavy thunderstorm activity, and neither appear to be a danger to develop.

Conditions may remain quiet in both the Atlantic and Eastern Pacific through the weekend, as well. According to the latest MJO forecast from NOAA, the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), a pattern of increased thunderstorm activity near the Equator that moves around the globe in 30 - 60 days, is currently in a phase that favors tropical cyclone formation in the Western Pacific. With the MJO in this phase, tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic and Eastern Pacific tends to be suppressed. The forecast notes that the MJO is expected to weaken and retrograde (move westward), which would tend to favor greater odds of tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic as soon as next week.

|

| Figure 3: The Saharan Air Layer (SAL) analysis from 11 am EDT Wednesday, August 2, 2017, showed a tropical wave that had just emerged from the coast of Africa, lying to the south of a large area of dry Saharan air. Image credit: University of Wisconsin CIMSS/NOAA Hurricane Research Division. |

The next foreseeable threat: a new African tropical wave

The next significant threat in the Atlantic would appear to be a tropical wave that emerged from the coast of Africa on Wednesday morning. The wave was under moderate wind shear of 10 – 20 knots on Wednesday morning, and had ocean temperatures marginally favorable for development: 27°C (81°F). The dry air of the Saharan Air Layer was to the north of the wave, but not close enough to seriously impede development. The 0Z Wednesday run of the European model predicted development of this wave occurring early next week in the Central Atlantic, as the wave moved west at 15 – 20 mph towards the Lesser Antilles Islands. The 0Z Wednesday run of the UKMET model also supported some limited development of the wave occurring early next week. The wave had support for development from about 40% of the 50 ensemble members of the 0Z Wednesday run of the European model; most of the forecasts showed the system arriving in the Lesser Antilles in the August 8 – 9 time frame. The GFS model did not develop the wave in its 0Z Wednesday and 6Z Wednesday runs. We give this wave 5-day development odds of 10%.

Bob Henson co-wrote this post.